When it comes to your book's recommendability and success:

It doesn't matter how much brilliance you've put into your book.

It matters how much your readers are getting out of it.

Beta Reading is how you measure that, ensuring that your book is not just well-written, but well-received.

Beta Reading is a relatively new addition to the author's arsenal, so there are plenty of myths, misunderstandings, and fears about it. In this guide, we're going to bust those myths and show you how to do it right, so you can unlock the high-impact reader insights that will help you make a better book.

At least in my experience11Hi, I'm Rob Fitzpatrick. I've written three nonfiction books that have sold about 300k copies and done about $1.3 million in royalties. That hasn't come from a big author platform (I don't have one) nor loads of hands-on marketing (I don't do any), but thanks to recommendations from happy readers. And those happen largely due to Beta Reading., Beta Reading is the single most important tool in the indie author's arsenal, and I'll never write another book without it.

In this guide, we'll cover:

-

What Beta Reading is, how it works, and why it’s different from just “asking for feedback”

-

What to do about negative (and positive!) feedback, and how to use it to make a better book

And, listen — I understand that the whole idea of Beta Reading can be scary. Beta Reading is a huge milestone — it’s supposed to feel like a big deal.

I was crazy nervous when I sent out my very first unfinished manuscript to real readers, way back in 2012. But once their feedback started coming in, and I saw how much it would help, I was hooked. (And that book's ongoing success is a direct result of the feedback I got.)

I won't try to claim that you aren't supposed to be a bit jittery. But what I can do is show you how to do it safely and properly, so you get the most benefit with the least risk. And if you’re willing to get over the fear and give it a try, I promise that your book will be better for it.

Get this article + bonus videos and templates delivered to your inbox

Beta Reading is like revising, but better

A major misconception about Beta Reading is in treating it as a sort of crowdsourced copy editing. It's not.

Beta Reading happens earlier than that, while you're doing your big revisions. In other words, after the first couple drafts, but before getting into detailed copy editing.22Rough drafts tend to be too messy to elicit useful feedback, whereas if you wait until you're copy editing, then it's too late to use the feedback to make big changes.

This particular moment, while the whole structure is in flux, is when you have the most leverage to make a better book. As such, you want to use your Beta Reading to identify problems that are bigger-picture and more existential than just typos and tone.

In particular, you want to know:

- Which bits are already working well, so you can stop fiddling with them

- Which bit is acting as the next "book killer" that's causing readers to disengage, drift away, and disconnect

This focuses your efforts during your next revision, such that you are spending more of your time and energy on the stuff that matters most — and ideally none of your time and effort on stuff that doesn't matter.33It's honestly a bit shocking to look back at how I wrote before I started Beta Reading and see how much of my labor was absolutely pointless: either fiddling with something already good enough, or obsessing over nuances of something that would be deleted anyway, like rearranging deck chairs on the Titanic.

The process of "doing Beta Reading" just means that instead of doing all your rewrites and revisions in the dark, you're taking a brief pause between each version to figure out what's working—and what's not—so far for your readers.

As a result, despite looking like an "extra" task that's going to slow you down, Beta Reading can often speed you up instead.

Beta Reading isn’t just “asking for feedback”

To receive useful insights, you'll need to ask the right people in the right way.

If you just "ask for feedback" from friends and family, they’ll tend to offer heartfelt, vague-ish praise. That's all well and good, but it doesn’t help you make a better book. (Or they'll just point out every typo, which is equally unhelpful.)

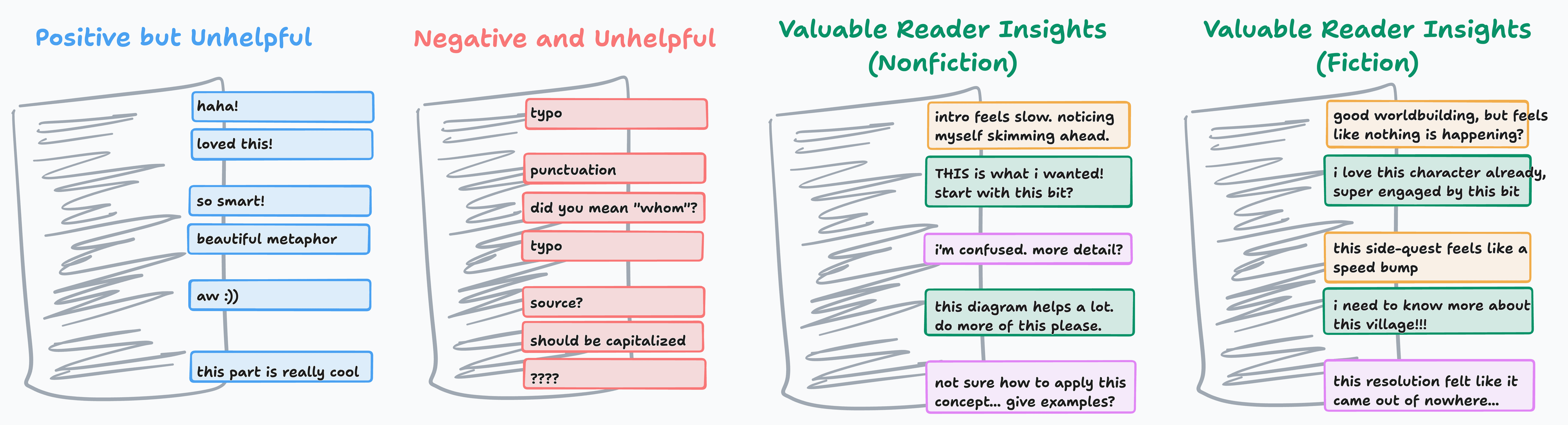

Fig 2. Examples of unhelpful vs. helpful feedback.

You don’t need to hear “It was pretty good!” or “There was a misspelling on page 17.” You need to know what’s working—and what’s not—for the type of person who will eventually buy and read your book.

Which all starts with finding and inviting the right sort of reader.

You don't need as many readers as you think

I see a lot of authors blocked by the belief that they need to find hundreds of Beta Readers to get any value out it. This simply isn't true.

It turns out that you can fairly reliably direct your next revision with as few as 3-4 qualified, engaged readers.

"Qualified" means that they're the right sort of person to provide useful feedback. Which means that they need to be the same sort of person as your future readers! You want Beta Readers who would be interested in buying and reading the book you are writing, even if it wasn't written by you.44As you progress through multiple rounds of Beta Reading, your readers will start to show signs that your book is getting really, really good. At that point, some authors like to start opening up their Beta Reading more widely, inviting anyone and everyone, and treating it as sort of early access component of their pre-launch marketing. That's a great tactic, once your manuscript gets good enough. But earlier on, while you're still trying to get there, it's better to be fairly picky about who you hear from.

"Engaged" means that they actually make an attempt at reading the thing. To count as "engaged," a reader needn't finish the book, but they do at least need to start it. This is just a numbers game. People are busy, and my experience has been that only about 1 in 4 of the people who say they want to read it will actually end up engaging in any meaningful way. To account for this, you’ll need to ask about 10-12 of the right sort of people to end up with 3-4 who will actually engage.55While the dis-engagement of a previously active reader is a valuable data point, you shouldn't interpret an invitee's non-engagement (i.e., they don't even begin) as any sort of rejection or critique. People are just busier than they think, despite their best intentions. (If you've invited 10 people and nobody is engaging though, then you may want to tweak either how your book's promise is presented, or the way you are making your invitations; more on both points shortly.)

Fig. 3. Expect to invite about 4x as many readers as you need.

With that as your goal, you don’t need a huge list or fancy email automation. You just need to send some emails.66If you do happen to have a relevant audience, you can accelerate the process by asking your list to opt-in to the idea of Beta Reading, while also telling you how early (and messy) of a version they'd like to be invited to. Once you've got these opt-ins, just invite a dozen or so more from the appropriate "messiness tier" whenever you could use some extra eyes on the manuscript. More details, and an invitation script, in this article.

Start small and personal

Here's how I like to do it:

Once I'm ready for Beta Reading, I sit down at the start of each day and think of one person who would really, truly want to read the book I'm writing.

I then send them a hand-typed, personal invitation to do so, without any awkward pushiness or pressure. (See the next section for exactly what my messages say.) With that one invitation sent, I close my inbox and go back to working on my book.

After 2 weeks of doing that small, daily task, I've sent 10-14 invitations and ended up with 3-4 engaged readers. (Plus connecting or reconnecting with a bunch of great people.)

That's literally how I start.77Later on, as my manuscript improves across multiple rounds of Beta Reading, I begin casting a progressively wider net with my outreach and invitations, which eventually transitions quite naturally into the activities of seed marketing and launch.

No big audience, no public announcement, no social media, no drama. Just one short email per day, sent to a person I think might care.

Fig 4. Inviting a Beta Reader. (See below for text versions of these emails.)

Email scripts for inviting Beta Readers

I don't think I'm especially unusual in that, while working on a book, I tend to talk to people about it. Sooner or later, someone will respond by saying that it's something they're actively trying to learn.88Or, alternatively, that it's a genre of fiction that they absolutely love, can't get enough of, and can't stop reading.

Which leads quite comfortably into an invitation like this:

Or as a more exploratory, open-ended message:99You'll notice that my scripts are non-pushy to a degree that might be seen as suboptimal. I do that on purpose. After all, the last thing I want is to "convince" someone into "doing me a favor" of providing detailed feedback on a book they wouldn't have wanted to read in the first place. Because then I've got to navigate through a bunch of feedback that looks all deep and insightful, but which is actually from a non-reader! So one of the ways I filter for qualified readers is to frame the request in such an easy-going, zero-pressure way that I'll only end up hearing back from the people who really, truly do want to read it.

This second sort of invitation often ends with, "No, but you should try reaching out to..." Which then sets you up to send a variation of the first message to the new person.

As your book progresses, you'll eventually "use up" your personal network, but that shouldn't worry you. Once your book begins to gain momentum1010The "momentum" of Beta Reading can sound a bit wishy-washy, but I've witnessed it for so many authors that it has to be real. I think two things are behind it. First, when you start seeing hard evidence that real readers really love your book, you become a whole lot more comfortable talking about it in public, which is a phenomenon also known as marketing. Second, when a person receives massive value or enjoyment from an unreleased manuscript, and when they've also helped to make it better, they can develop a strong sense of ownership that cranks their evangelism up to 11. Not to mention, it's pretty compelling to be able say, "Here's what my readers said was wrong with my book, and here's how I've fixed it, and now you can read the newest version, if you want to.", you'll start finding new Beta Readers as a byproduct of working on the book itself (especially if you're writing in public).

Once you've got the right people in your manuscript, you need to draw the right conclusions. So let's look at what they say — and don't say — and how to figure out what it all means.

Figuring out what's already working

As a reminder, we're trying to learn two things from Beta Reading:

- Which bits are already working well, so you can stop fiddling with them

- Which bit is acting as the next "book killer" that's causing readers to disengage, drift away, and disconnect

The part that's working well is usually pretty simple to figure out. First, readers will often straight up tell you that they loved it, they tried it, and it worked. (Or they'll keep asking you when the next chapter will be ready.)

Second, instead of readers quietly drifting off and disappearing, you'll see that they've continued reading and commenting on later chapters.1111Assuming that you've been careful to avoid any perception of pushiness in your invitations (see above), you can actually get a LOT of information by just looking at how much of the book a person has finished reading. As a rule, reading an unfinished manuscripts is hard work. If someone is making the mental effort to persevere to the end, it's usually safe to bet that they're getting something valuable out of it, even if they haven't said so.

All-in-all, you really don't need to overthink the positive side of this. It's pretty self-evident once your book starts working.

Still, if you want a checklist to aim toward, you ideally want to see these signs:

- It feels easy to find new Beta Beaders, since people quickly "get" what the book is about, and at least some of them can't wait to read it

- At least a third of your engaged readers are reaching the end, and there's aren't any "cliffs" where you're losing a huge percentage of your readers at a single point

- For useful nonfiction, at least some of your readers have given it a try and gotten results1212Which you figure out by following up with happy readers.

- For fiction, at least some of your readers have signed up to receive new chapters and sequels

- And in a perfect world: at least some of your readers are telling their friends, some of whom are asking you if they can be Beta Readers

Fig 4. Reader data from Help This Book, showing a worrying drop-off after Chapter 4.

Finding and solving the "book-killers"

The worst time to find out about your book’s problems is in an Amazon review.

—Nir Eyal, million-copy author

A "book-killer" is an issue that will dramatically harm your book's odds of success if left unresolved.1313In many cases, it's the thing stopping your current round of Beta Readers from reaching the end of the book. Not necessarily because of any obvious disaster, but simply because a chapter somehow ended up feeling like too much of a slog to get through, so readers drift away. That's exactly the sort of thing that's hard to notice on your own, but becomes crystal clear once you've got some real readers in there.

Each of your revisions should be undertaken with the goal of resolving a specific book-killer.

With each round of Beta Reading, your book will get better and your readers will get further. Before too long, your whole book is working brilliantly.

As mundane as it sounds, these book-killing problems will appear in your data as a critical mass of two little emotions:

- This feels slow

- I'm feeling confused

And, if you're writing useful nonfiction, you're also very interested in the presence (or absence) of:

- I can use this!

By combining these reactions with your observations of where people stop reading, you've got everything you need to figure out what to fix next.

If most of your readers are abandoning the book at Chapter 5, there’s no need to rewrite anything past that point. Use their feedback to figure out what’s stopping them, revise your manuscript to improve it, and run another round.

Readers spot the problems; you design the solutions

If a bunch of readers are saying that some chapter is slow and confusing, and then they all stop reading, you probably want to take that pretty seriously. There's 100% a problem there.

However, some of those readers will also provide suggestions (and sometimes demands) about what you ought to change to make it better. They'll tell you to add stories, redo diagrams, change the tone, and so on. IGNORE IT.1414As an amusing example from the world of fiction, Brandon Sanderson once shared that Beta Readers for one of his Stormlight books were reacting with violent negativity toward a multi-chapter, half-cast side-quest. They said those chapters were slow, terrible, boring, and needed to be deleted or at least rewritten. What Sanderson did was to acknowledge the reality of the problem ("okay, readers are finding these bits boring") and then calmly design his own solution. Which involved (...drumroll...) adding a couple sentences to the beginning of the side-quest, clarifying its do-or-die relevance to the primary narrative. Just like that, readers stopped saying it was slow, stopped saying it was stupid, and started loving it. Sanderson resolved a 20,000 word "crisis" with 200 words of framing.

The job of reader feedback is to help you see your book's problems, as a reader would experience them.

The job of you, the author, is to decide how you want to fix them, which you'll take a stab at with your next revision.

How long it takes

I like to allow two weeks for a single round of Beta Reading, which inviting a batch of readers and then allowing them time to provide their feedback.1515I've found readers tend to give feedback either fairly soon, or not at all, so there's not much benefit to waiting longer.

Of course, once you've gathered the critical "what to fix" feedback, you'll still need to take however long you take to integrate it into a new revision.

The early revisions tend to be faster, since if your readers are finding a bunch of problems in Chapters 1 and 2 before giving up, then you only need to revise those chapters.

With each round, your book will get better, and your next set of readers will get further through the manuscript as a result.

Once you start seeing that readers are reaching the end and getting the value, you'll know that your book is working — that it is Desirable, Engaging, and Effective — and that you're ready to call Beta Reading a big success, and shift yourself into the more detail-oriented work of copy editing and proofreading.

Fig 1. A successful reader journey.

Tools you’ll need

It’s essential to get readers to leave feedback inline, as they read. If you ask them for reactions after they’ve read the whole thing, they will have forgotten most of their thoughts and you’ll get generalized impressions.

There are a few approaches that satisfy this requirement.

You could print the manuscript and send it to readers, with some nice pens and a return envelope. But this will extend your timeline considerably, and removes the possibility of seeing all your feedback in one place.

Another option is Google Docs — you can share one link with all your readers, and see all their comments together. The downside here is that every piece of feedback is a comment, and if you get enough of them they can be overwhelming. In addition, you can’t really impose much structure your readers’ input — you can ask them nicely to focus on what’s useful, boring, or confusing, but you may still end up with a lot of typo corrections.

Google Docs works — can also get noisy.

The option we recommend — since we built it for this purpose — is Help This Book. For your readers, leaving feedback is simple, and structured. We measure reading time, and give you a graph of reader progress — so you can find out where you’re losing them. You can control who has access, and whether readers see each other’s comments. And all the feedback is collected in one place where you can track it, filter it, and export it with a single click.

Help This Book sorts feedback by reaction type, chapter, and reader.

How to start today

If you've already got a manuscript, your next steps are to get it ready to share (we suggest using Help This Book), then invite your first reader.

If you haven't written anything yet, start by writing and sharing a mini-manuscript — it only takes about a week to produce something beta-readable.

Congratulations, you did it!